Sasanian Plate. Ex Burnes Collection

Image source: Plate 11, Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period. Vol. 1, Royal Imagery, by Harper, Prudence O., and Pieter Meyers

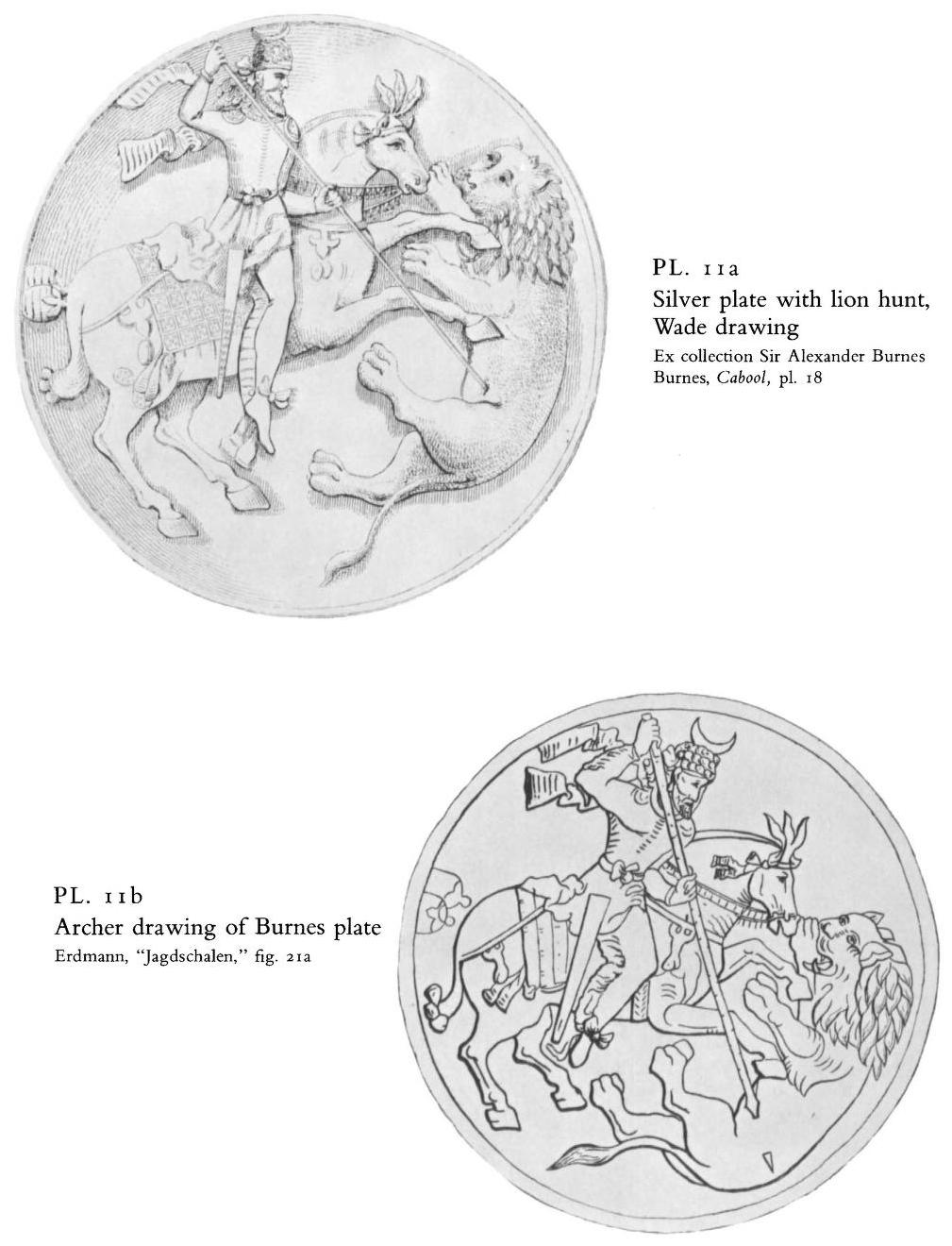

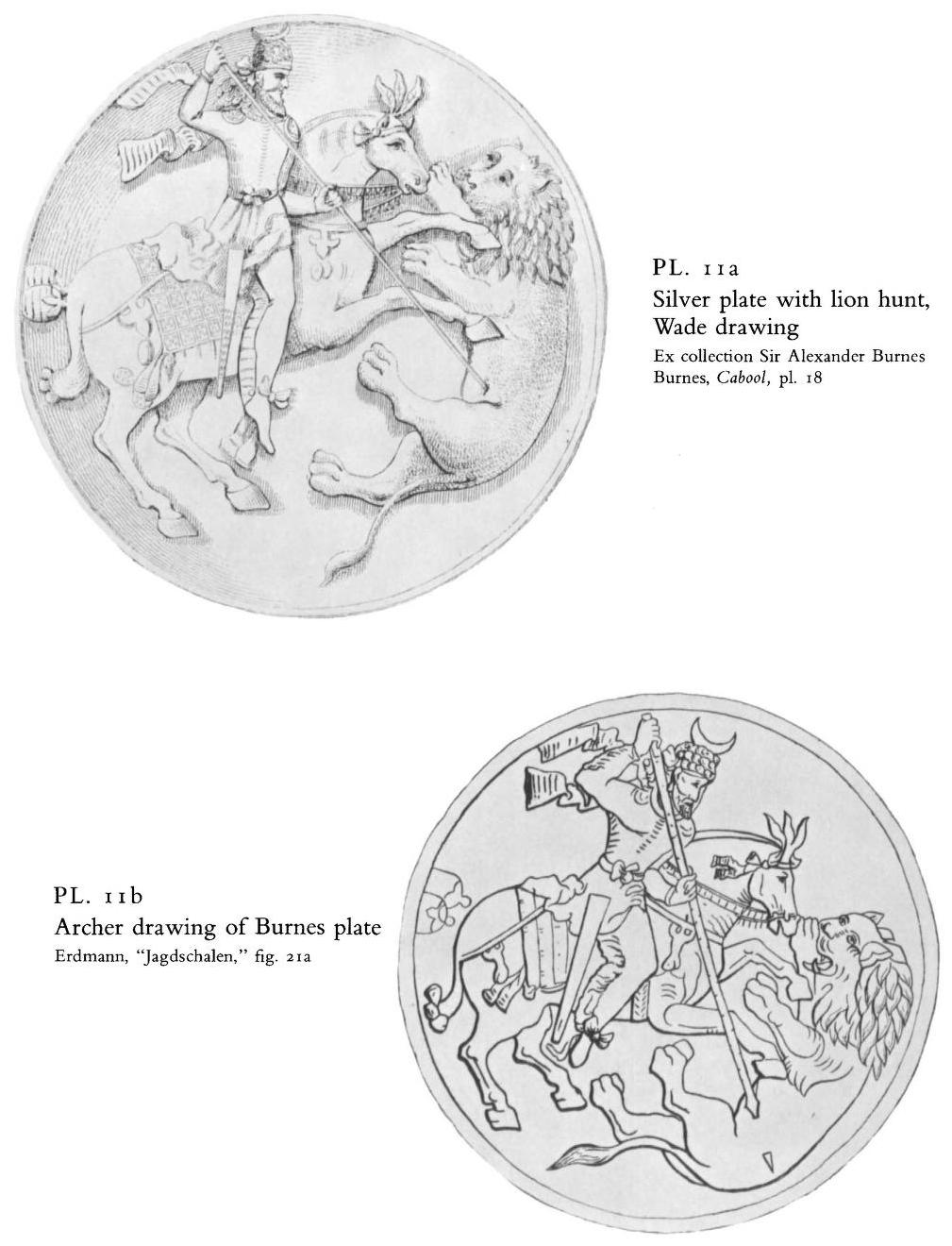

Burnes plate (PL. 11). The final complete vessel belonging to this group must be more summarily treated, as it is known to us only from drawings made in the first half of the nineteenth century. The piece itself disappeared when its owner, Sir Alexander Burnes, was murdered in 1841 in Afghanistan. Allegedly once in the collection of the Emir of Badakhshan, it was brought with another plate to Kabul by Dr. Percival B. Lord and at his death entered the Burnes collection. In spite of this evidence of an Eastern provenance outside the borders of Sasanian Iran, the plate is included here because it has a Middle Persian inscription giving its weight. It shares, as well, a number of formal characteristics with the plates already described. The vertical position of the hunter is balanced by the nearly vertical figure of the quarry, a single lion. As with the Sari plate (Pl. 10), the hunter is in right profile. Entirely new, however, is the rearing position of his mount, understandable because the figure of the lion faces toward rather than away from the horse. The front hooves of the horse cut slightly into the lion's body. The strong oblique line of the spear suggests for the first time the triangular form of composition that Erdmann traced in a number of the royal hunting plates, among them this one.84 As both drawings indicate, the entire scene does not quite fit within the circular surface of the plate, for parts of the horse trappings, the balls of hair, are cut off by the vessel's rim. In neither drawing are any landscape elements included in the design.

In his dress, this hunter is closest to the figure on the Shemakha plate (Pl. 8). Only the headdress is rather different, consisting simply of a crescent, shown full-front, resting on the top of the profile head, which is left bare and covered with tight curls. The ends of the long ribbon around the head, and the necklace, earring, and circular shoulder patches, are closely related on these two vessels. The belt was evidently tied in a bow as on the plate from Sari (Pl. 10). Ribbons and bow appear on the foot below the soft material of the leggings. A quiver hangs from a strap at the hunter's waist, and, in the Wade drawing (Pl. 11a), appears to be at least partly covered with a pattern of zigzags.

The forelock of the rearing horse is drawn up above the head in three separate bunches or tufts. The mane is cut short, the tail tied in a bow. Both reins have pendants of some sort hanging from them, as on the Sari plate (Pl. 10). Suspended from the straps across the chest and rump are two palmette-shaped elements from which oval pendants hang. On the rump the strap cuts across the saddle blanket in the same fashion as on the Krasnaya Polyana plate (Pl. 9) and to a lesser degree on the Shemakha vessel (Pl. 8). Decorating the blanket in the Wade drawing (Pl. 11a) is a checkerboard pattern, the large squares enclosing a design of five circles. On the Krasnaya Polyana plate the blanket is also divided into squares, but these contain circles arranged around a central point. From the corner of the blanket on the Burnes plate hang the usual ribbons. The girth is shown in both the Archer and Wade drawings. On the Archer reproduction (Pl. 11b) the girth has a chevron pattern, as on the Shemakha plate. On the Wade drawing (Pl. 11a) there appears to be a double row of pearls. No details of the large hair balls projecting in the customary fashion from the back are given in the Archer drawing. Wade, however, drew horizontal lines across them, undoubtedly to give the waved effect produced by such lines on the vessels from Krasnaya Polyana and Sari.

The body of the lion may have been covered by hatched or dotted lines. This is at least suggested by the Wade drawing (Pl. 11a). However, the elaborate treatment of the lions' manes on the Sari plate (Pl. 10) could not have existed on the Burnes plate, since there is no indication of it on either drawing; instead there are only simple tufts. The position of the lion is similar to that of the goat on the Shemakha plate (Pl. 8). The animal's back is against the rim of the plate in an awkward fashion, his legs beneath his body. On these two vessels the single animal is pierced by the weapon and must be supposed to be dead.

Erdmann in his consideration of the plate in the Burnes collection left open the question of whether it was an original work of the third century, possibly even pre-Sasanian, or a later work imitating plates of this early period.88 A number of the details described above place it, as will be apparent at the end of the present survey, in Group I, consisting of works belonging to the earliest period. More difficult to prove, in view of its provenance and the fact that only drawings exist, is whether the piece was executed by Sasanian craftsmen or not. For the time, it is included in Group I because of the presence of a Middle Persian inscription and because in so many respects it is related to the other works in this category.

Summary. All these plates (Pls. 8-11) share in common a number of features also to be seen on the early Sasanian rock reliefs of Firuzabad, Naqsh-i Rustam, Bishapur, and other sites. The form of dress and the horse trappings are in general the same. More specific are the resemblances in the decorative trim of the horse's mane, the bowed tail, the Sari type of bit (Pl. 10), the rows of circular phalerae, the ribbons projecting from the saddle blanket, the leg guard of the saddle, and the broad folds of the hunter's garment where it rests on the back of the horse. The triangular composition of the Burnes plate (Pl. 11) is related to that of the Sar Meshed relief.87

81. See note 71 above.

82. Diam. 28 cm. For bibliography up to 1936, see Erdmann, "Die sasanidischen Jagdschalen," pp. 226-227, note 4. The best reproduction of the Wade drawing appears in Burnes, Cabool, pl. 18. Erdmann, "Zur Chronologie," p. 240; Erdmann, "Entwicklung," p. 102, note 59. In the last article Erdmann says the plate may be an Arsacid work, a view he had already expressed in "Zur Chronologie." Marshak and Krikis, "Chilekskie Chashi," p. 63. The king is identified as Yazdgard I, and the plate is placed in Marshak and Krikis' fifth stage.

83. Livshits and Lukonin, "Nadpisi," p. 163.

84. Erdmann, "Die sasanidischen Jagdschalen," p. 227.

85. Erdmann notes that a diadem with crescent is a form of headdress appearing on the pre-Sasanian coins of Persis: "Zur Chronologic," p. 240.

86. Erdmann, "Die sasanidischen Jagdschalen," p. 227.

87. Hinz, Altiranische Funde, pl. 134.

Source: pp. 55-57, Silver Vessels of the Sasanian Period. Vol. 1, Royal Imagery, by Harper, Prudence O., and Pieter Meyers