In Byzantine representations, we find lamellar armour whose rows are separated by narrow bands44. Dawson assumes that this is the leather band placed between the rows, separating the plates and neutralizing the scissors effect caused by their movement, which may cut the thongs45. Subsequently, further developing his observation, Dawson came to the conclusion that in Byzantine lamellar armour it is not a narrow band of leather that is placed between the plates but wide leather fully lining the plates. Such armour is more flexible horizontally46 and is easy to make. Later its making was simplified further by riveting the plates on to the leather (instead of fixing them by means of thongs) 47. Dawson believes that in Byzantium lamellar riveting came into use in the 11th century48.

44. Scholars note that early representations of banded lamellar are attested in Central Asia as early as the 8th-9th centuries. HALDON, Some Aspects of Early Byzantine Arms and Armour, 79. But it is not the construction occurring in the Georgian-Byzantine lamellar armour (if it is of metal, in general). Here we are dealing with the leather band covering the edges of the armour plates. However, the basic idea of combining metal plates and leather in lamellar armour must have entered this region precisely from Central Asia.

45. T. DAWSON, Banded Lamellar - a Solution, Varangian Voice 23 (1992) 16.

46. However, in my opinion, owing to the absence of horizontal overlapping, it must have been weaker. In any case, the suspended lamellar rows covered almost half of the length vertically, which means that in order to penetrate into the body the weapon had to pass through two layers of armour. DAWSON, Kremasmata, Kabadion, Klibanion, 45.

47. In the representations the riveting is indicated by a bullet point.

48. DAWSON, Kremasmata, Kabadion, Klibanion, 44-45.

p72

In the 11th-12th centuries, besides riveted, inverted lamellar also comes into use: the armour sleeves and the skirt are made of inverted lamellar plates, i.e. they are distributed upside down. Ordinarily, lamellar plates overlap from below upward, as arranged in this way they provide best protection of the body from piercing strikes, that are, as a rule, directed upward. But the limbs mostly receive strikes from above. On the limbs, protected with inverted lamellar, the strike slides downward, inflicting less damage49.

Dawson's surmise about the emergence of banded lamellar in the 11th century is supported by Georgian data too: in 10th-century representations, the common lamellar is depicted, beginning with the 11th century the banded one appears50. It is noteworthy that this phenomenon was not overlooked by art historians in Georgia (explanation of which clearly exceeded the boundaries of their competence). As early as in the 1980s, T. Sheviakova wrote that the appearance of narrow bands between armour plates was observed in Georgia from the 11th century51.

A careful study of representations of lamellar suits led me to the conclusion52

49. DAWSON, ibid. 46-7; ID., Suntagma Hoplon, 89.

50. Maria G. Parani generally believes that Byzantine lamellar bands are the result of the artists' imagination; they have nothing in common with reality and come from erroneous conveying of the shadows cast by the plate rows. In order to prove this view and to refute Dawson's opinion, she points to the existence of a lamellar without bands. MARIA G. PARANI, Reconstructing the Reality of Images: Byzantine Material Culture and Religious Iconography (11th-15th Centuries), Leiden, Boston 2003, 107. I cannot share Parani's point of view; the existence of bandless and banded (also linear) lamellar is indicative of different stages of their development and evolution. The wall paintings of Timotesubani convincingly speak in favour of this idea; in these murals the master depicted side by side banded armour and that with shadows under the plates (precisely like the one Parani speaks of); furthermore, in one of the frescoes [fig. 1] both the bands and the shadows are painted together, which excludes the artist's mistake and indicates that the lamellar band was not used to represent the shadow. Parani too is well aware of the existence of such representations.

51. T. S. SHEVIAKOVA, Monumental Painting of Early Medieval Georgia, Tbilisi 1983, 23 (in Russian).

52. Due to the paucity of archaeological material, I have to limit myself only to the observation of specimens of art. I am well aware of the problems such an approach may create and also know that a final conclusion can be made only when additional archaeological data have come to light. Unfortunately, all the researchers into Byzantium and the East of this period have to face the same problems. On such difficulties connected with Byzantine studies, see PARANI, Reconstructing the Reality of Images, 101-2.

p73

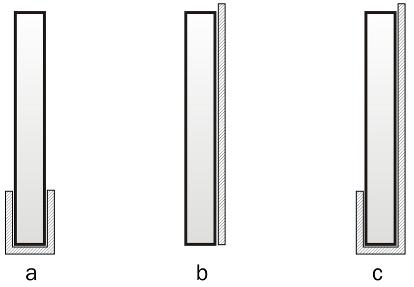

that we should distinguish between the so-called banded53 and linear54 suits of armour. Since the appearance of these two types of armour are distanced from each other in time too (banded lamellar appears only in the 11th century, while the number of linear ones is great back in the 10th century), it is difficult to ascribe the differences between them only to the interpretation or imagination of their executors. We should rather assume that there was a certain difference in design between them and try to identify the differences. In my opinion, between plates there appears to be one line in the case when the row of plates have a leather lining only in the rear55; in banded lamellar the leather lining is behind the plates and the lower part of the plate is also lined [fig. 3c] It must not have been difficult to arrive at the method of covering the plates in this manner. As a matter of fact, it unites in itself the old method of lamellar construction spread in Asia (when a strip of leather covers the plate edge)56 and the other, comparatively new technique (lining the plates with leather at the rear) [fig. 3] Combination of these two methods yields a banded lamellar, when the band is clearly visible (the edge of the leather

Fig. 3. Side view of the lamellar plate: a) with the leather covering the edge, b) with leather backing, c) with leather backing and encasing the front lower part of the plate. |

53. When the band between the armour plates is formed of two distinct, upper and lower lines. Such are the icons of Ipari, Shodai, Labechina and St George of Supi, also the frescoes of Warrior Saints of Ipari, Lagurka and Nakipari and many others.

54. When only one line can be seen between the armour plates. Such are St George and St Theodore of the Chukuli icon, St George and St Theodore of the Mravaldzali icon, the Parakheti St George icon and others.

55. It is precisely this type of armour that is the result of Dawson's method: the leather lining placed behind the plate does not form a band.

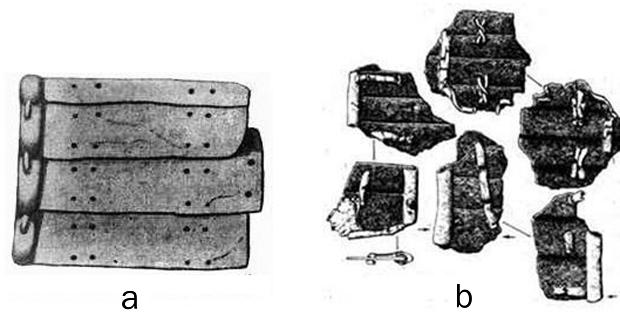

56. Along the perimeter of the lamellar rows, a leather strip was fixed enfolding the plate edges. It strengthened the structure and protected from traumas that might be caused by the sharp edge of the armour. Such are the remnants of 10th-12th-century lamellar found in Ust’-Ishim. SOLOVIEV, Art of War, 51, pl. XI, 5. In fig. 2, the leather enfolding the plate edges can be seen well. The 4th-5th-century armour plates, found in Berel by v. Radlov are almost similar. A. A. GAVRILOVA, The Burial Ground of Kudyrge, as a Source for the History of the Altai Tribes, Moscow-Leningrad 1965, 55, fig. 4.13 (in Russian). This similarity between armour plates, separated by several centuries, may be indicative of the fact that in a greater part of Asia the lamellar construction did not undergo great changes and that the evolution of the lamellar started in Byzantium and in Georgia in the 10th century must be a comparatively isolated occurrence. In addition, we can note 6th century lamellar plates with enfolding leather found in Viminacium, which means that the Byzantines were well aware of the Asian type lamellar design. I. BUGARSKI, A Contribution to the Study of Lamellar Armours, Starinar 55 (2005) 168, 171.

Fig. 2. a) Armour plates found in Bereli, after Gavrilova (fig 4.13); b) Uust’-Ishim lamellar plates with leather, after Soloviev (pl. XI, 5). |

p74

covering the front of the upper plate forms the upper line of the band, the piece of leather lining the lower plate creates the lower line of the band). In this case the thongs are completely safe from being cut by the plates, the clothes worn under the armour are not damaged either; the wide piece of leather which also covers lamellar plates from the front facilitates greater stability and firmer linkage. It should be noted that the lowest row of lamellar plates, which borders on the kremasmata, is emphasized by a band at the bottom, which must be indicative of the leather enfolding the lower part of the plate57.

It must be said from the start that examination of Georgian material enables us to follow the evolution of splint armour, its definite stages and numerous experiments which will be discussed below.

In order to illustrate the road covered by the Byzantine-Georgian lamellar, it would be good to present its prototype, lamellar of the original design, for which we may refer to the Timotesubani fresco, depicting a Warrior Saint58. In this picture [fig. 4] the saint is clad in a traditional lamellar cuirass. The lamellar rows consist of laced plates, without riveting, overlapping from right to left; the lamellar rows are linked with numerous suspending thongs and overlap from below upwards. Such was the typical lamellar, in which changes took place almost simultaneously in the Byzantine Empire and the Georgian kingdoms.

In the 10th century, several experiments are noticeable in Georgian (rejection of horizontal overlapping, introduction of leather lining and riveting); these were the first steps taken in the evolution of splint armour. An earlier date of these experiments cannot be excluded either, but we can speak decisively only about the 10th century, when their reflection in the works of art was firmly established.

The introduction of the leather lining between the lamellar rows can be seen clearly on the armour of St George and St Theodore depicted on the 10th-century triptych of the Virgin preserved in the church of Chukuli59 [fig. 5]. Lamellar plates are fixed to the leather lining, the plates do not overlap

57. It is seen well on the frescoes of St Theodore and St George of Nakipari, on the Adishi Warrior Saint's fresco, the Labechina icon of St George on foot and others.

58. Belonging indeed to a later date, but suitable for demonstration.

59. G. N. CHUBINASHVILI, Georgian Repoussé Work, Tbilisi 1959, 409-10, pl. 46 (in Russian); M. AKHALASHVILI, 10th-15th-century Inscriptions on the Monuments of Repoussé Work in Svaneti, Tbilisi 1987, 8 (in Georgian).

p75

horizontally but are packed close together. A lamellar made by this method is more flexible, is easy to prepare, economizes 15-20 percent of the material and accordingly reduces the weight of the armour60.

The introduction of riveting is attested in the same 10th century, it was apparently used in both types (scale and lamellar) of splint armour. On the Chikhareshi triptych of the Holy Virgin St George and St Theodore61 [fig. 6] and two representations of St Theodore62 depicted on the cross of the Saqdari church are clad in splint armour with two (upper and lower) rivets. Presumably it is scale armour, as it is furnished with long sleeves, which are absent in lamellar armour63.

On the Nakuraleshi St George icon64 [fig. 7] the plates with two (upper and lower) rivets are presented as lamellar armour, where the rows overlap from below upwards. It may be assumed that the suspending thongs of the rows are fixed from the rear to the fastening thongs located on the lower edge of the plates65; however, a simpler explanation may be found, if we assume that on the repoussé icons the plates are represented in a slightly simplified manner and they lack the suspending thongs. Plates of this type can be seen in the miniature 60r [fig. 8] of the Minor Synaxarion copied by Euthymius the Athonite in Constantinople in 103066. On the armour plates of St Procopius, the central lines are already discernable, these may be considered to be thongs which are probably absent on repoussé icons.

These types of riveted armour may be ascribed to the imagination of the artist or to an erroneous representation, but for one circumstance: the

60. DAWSON, Kremasmata, Kabadion, Klibanion, 44.

61. The Holy Virgin triptych of Chikhareshi church is now lost; my reasoning is based on the photo by Ermakov, N16879. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 411-2, pl. 47; AKHALASHVILI, Inscriptions, 9-10.

62. The chancel cross, erected in St George's church in the village of Saqdari, now completely stripped of its ornamentation; my reasoning is based on the photos by Ermakov, N16833 and N16847. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 341; AKHALASHVILI, Inscriptions, 13.

63. Though it also should be said that it is problematic to imagine a scale sleeve with such plate.

64. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 339-41, pl. 42.

65. Such a system of fastening occurs in the case of 'invisible' thongs. MAKUSHNIKOV - LUPINENKO, Lamellar Armour of the Eastern Slav Warrior, 216.

66. Manuscript A648 at the national Centre of manuscripts of Georgia. T. D. ZHORDANIA, Description of the Manuscripts of Tbilisi Ecclesiastic Museum, v. 2, Tiflis 1902, 132 (in Russian).

Fig. 9. Armour plate with two rivets, after Soloviev (pl. X, 5). |

existence of this type of plates with riveting is proved by the material of the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennia discovered by Russian archaeologists in Western Siberia. It transpires that fixing armour plates to leather by means of upper and lower riveting was an accepted method. This method was used by the Enisey Kyrgyz as well67 [fig. 9].

Two icons, uniting many signs of this evolution, should be considered a kind of summing-up specimen of the experiments taking place in that century.

The representations of St George and St Theodore [fig. 10] on the Mravaldzali icon68 dating from the latter half of the 10th century, and the Parakheti icon of St George of the end of the 10th century69 [fig. 11] show lamellar plates with double riveting and a double suspension on the leather lining; the plates do not overlap, but are arranged very close together side by side. Practically here all the basic components of the evolution of lamellar armour are present; the only component that is lacking is a wide band, due to which these suits of armour may be grouped with the category of linear lamellar70.

67. SOLOVIEV, Art of War, 51, pl. X, 5.

68. It was preserved in the Mravaldzali church of St George, now it is lost; my reasoning is based on the photo taken by T. Kuhne during E. Taqaishvili's expedition to Racha in 1919. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 406-9, pl. 36.

69. It was taken from Parakheti to Mravaldzali; my reasoning is based on the photo taken by T. Kuhne during E. Taqaishvili's expedition to Racha in 1919. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 342-3, pl. 43.

70. The kremsamata of the Warrior Saints evokes interest, with large plates directed downwards. The reinforcement of a skirt, made of cloth, with metal plates in order to protect the limbs, was introduced into Georgia back in the 10th century, which will shift this date for Byzantium as well. Examination of the icons shows that Dawson's conjecture that in the Byzantine world the infantryman and cavalryman wore similar armour skirts seems to be well founded. In order not to hinder their movement and activities, in both cases such a skirt was fastened in different ways; the infantryman turned the slit of the armour to the side, the cavalryman placed it between his legs (DAWSON, Kremasmata, Kabadion, Klibanion, 49). Both figures of St George, equestrian and on foot, depicted on the Parakheti and Mravaldzali icons wear exactly identical lamellar skirts, but with slits in different places. If this is the case, then here we are already dealing with Byzantine influence, as traces of high standardization must be sought in the state system of Byzantium and not in the feudal society of Georgia.

p 77

In the 11th century, search for 'the ideal splint armour' becomes more intense and diversified: a banded lamellar comes into use, the method of overlapping the plates downward (the so-called 'inverted lamellar') is firmly established, the number of the suspending laces changes; complex, ceremonial, luxurious suits of armour also become numerous.

The Nakipari icon of St George71 [fig. 12], made in the early 11th century, and St George depicted on the Samtavisi chancel cross72, dating to the 1st half of the same century, show a complete 'inverted' lamellar with double riveting: the klibanion73, the kremasmata74 and the manikia75 comprise plates directed downward. The armours differ from one another only in the number of suspending thongs.

Also at the beginning of the 11th century the first specimens of banded lamellar appear. It is noteworthy that the Ipari icon of St George76 [fig.13], dating from the 1st quarter of the 11th century, shows banded lamellar plates without riveting. This icon, as well as the Labechina icon, representing St George on foot77, and the Shodai icon of St George78, make it clear that lamellar with riveting is not popular yet.

An interesting attempt at blending banded and riveted lamellar armour is shown on the Labechina icon of equestrian St George79, [fig. 14], dating from the second decade of the 11th century. Here on a banded klibanion (as well as on kremasmata) we see plates with (upper - lower) rivets of an earlier type, which later were completely superseded by plates with riveting in their upper part.

71. Asan Gvazavaisdze's work, done in his youth. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 363-7; AKHALASHVILI, Inscriptions, 21-2.

72. CHUBINASHVILI. Repoussé, 493-9, pl. 284.

73. Klibanion - short body armour of splint (lamellar or scale) construction. See T. G. KOLIAS, Byzantinische Waffen [BV, 17], Vienna 1988, 45-7.

74. Kremasmata - padded skirt for leg protection, often reinforced with metal plates.

75. Manikia - protection for the upper arm, from shoulder to elbow.

76. Made by Asan, commissioned by Marushi. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 358-63, pl. 184. AKHALASHVILI Inscriptions, 17-8.

77. CHUBINASHVILI. Repoussé, 261, pl. 56.

78. It was preserved in the village of Ghebi from the Shodi church of St George. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 367, pl. 95.

79. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 326-30, pl. 181.

p78

On the 11th century Supi icon of equestrian St George80 [fig. 15] a banded lamellar of typical riveted plates is depicted. The lamellar is completely (cuirass, skirt, manikia) 'inverted', which means that the experiment of the plates directed downward was also continued in the banded armour.

Finally, a great number of frescoes and specimens of repoussé work depict the already established type of lamellar armour which was most widespread in the 11th-12th centuries and in the following period as well. Its banded cuirass consists of riveted plates directed upward and the kremasmata and the manikia are formed of inverted lamellar plates. Such are the icon of Supi representing St George on foot81 [fig. 16], St George and other Warrior Saints [fig. 17] depicted in St George's (Jgrag) church in Adishi, clad in a typical banded lamellar with riveting.

Here I should like to dwell on a certain type of armour which more readily than the others could be ascribed to the artist's imagination, but due to the identity of its author and to its interesting structure it is worth discussing.

Frescoes made in the churches of Svaneti at the turn of the 11th-12th centuries by Thevdore, the court artist of David the Builder, King of Georgia, have come down to us82. Saints portrayed by Thevdore (equestrian figures of St George and St Theodore and the figure of the Archangel Michael in Iprari83, St Theodore of Lagurka [fig. 18] and St George and St Theodore of Nakipari84 are clad in similar suits of lamellar armour, which is distinguished by a rather strange design: it is a banded lamellar with riveting between (!) the plates, which fasten the leather of the lower row with the upper one.

80. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 443.

81. Repoussé, 563; AKHALASHVILI, Inscriptions, 40.

82. The churches, adorned wirh frescoes by Thevdore, are dated precisely thanks to the surviving inscriptions from which we learn his name and the time of the execution of the work. N. A. ALADASHVILI - G. V. ALIBEGASHVILI - I. VOLSKAYA, The Painting School of Svaneti, Tbilisi 1983, 30-2 (in Russian). The donor inscription of the Iprari church of the Archangel (Taringzel) reads: 'it was adorned with paintings in the year of 1096, by Thevdore, the King's artist'. Written Monuments of Svaneti (10th-18th centuries), ed. SILOGAVA, Tbilisi 1988, 70-1 (in Georgian).

83. ALADASHVILI - ALIBEGASHVILI -VOLSKAYA, The Painting School of Svaneti, pl. 24, 25, 27.

84. Ibid. pl. 60.

p79

If such a design did really exist it must have been more strongly linked85, though less flexible.

Apart from the fact that the status of royal artist demanded that he should adhere to certain standards, St Panteleimon's banded lamellar with riveting, depicted on the 12th-century processional cross of Pari86, may be used as additional evidence in favour of the armour painted by Thevdore [fig. 19]. Here, too, similarly to Thevdore's frescoes, we find rivets between the plates of the lamellar cuirass87.

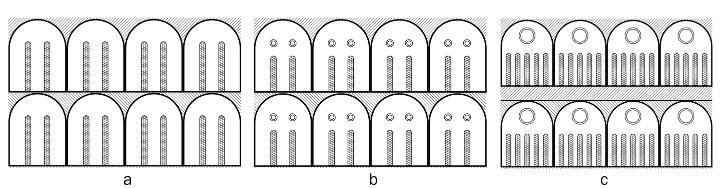

Fig. 20. a) First stage of the evolution of the lamellar armour – introducing leather backing (according to the Chukuli triptych), b) Second stage of the evolution – linear lamellar with double riveting (according to St George of Mravaldzali), c) Third stage – typical banded lamellar with riveting (according to the Adishi frescoes). Hatching oriented in different directions indicates the leather backing of different lamellar rows. |

Judging by the specimens presented above, the evolution of lamellar armour may be considered to have been completed [fig. 20]. Subsequently we no longer witness such diversity of splint armour. Nevertheless, individual experiments did still take place. In this connection interest attaches to the 13th-century fresco of St Theodore, preserved in the church of the Annunciation in the Gareja Monastery; the saint is clad in lamellar armour with a skirt made of plates with triple riveting88.

Interesting material on the closeness and resemblance between Byzantine and Georgian armour is provided by comparing one type of lamellar. On the 12th-century fresco of St Nestor in St Nicholas' church in Kastoria the saint is clad in lamellar consisting of rectangular plates with unrounded tops. The economy caused by such plates is not great but it saves much time when making the armour89. Many Georgian analogues of this type of Byzantine armour can also be found: on the Sakao icon of St George90, dating from the end of the 10th century, the saint is wearing the same banded lamellar91. The suits of armour of St George and St Theodore, depicted on the façade of St

85. In comparison with typical lamellar, where the rows are linked only by thongs.

86. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 524-5; AKHALASHVILI, Inscriptions, 37-9.

87. It is not ruled out that here overlapping plates were depicted, but this is alien to riveted lamellar. Such armour, unlike the typical one, must have been very heavy and unwieldy.

88. Monasteries of David Gareja: Lavra, Udabno, eds. M. BULIA - D. TUMANISHVILI, Tbilisi 2008, 116 (in Georgian).

89. DAWSON, Kremasmata, Kabadion, Klibanion, 48.

90. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 344-8; Georgian Goldsmithing in the 8th-18th Centuries, Tbilisi 1957, pl. 98 (in Georgian).

91. The difference is only in the number of rivets: on the lamellar plates of St George there are two rivets, on St Nestor's - only one.

p80

George's church in Adishi [fig. 21], the Armour of St George represented on the 11th-century Lanchvali92 and Seti93 icons, are also formed of rectangular plates, their tops left unrounded.

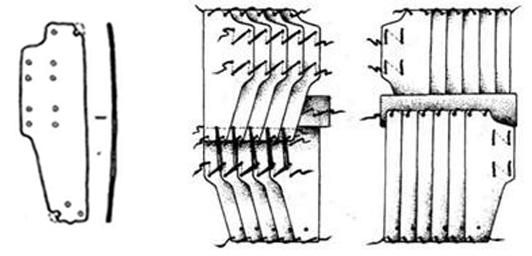

Another very interesting type of lamellar armour is depicted on Georgian repoussé icons and miniatures. Namely, the banded lamellar whose plates are rendered as thin, straight lines by the master. At a glance, such armour may be taken for the master's error, who did not take trouble to depict the plates meticulously and executed them in a simplified manner. Fortunately, archaeological finds from Belarusia do not allow such a conclusion, attesting once more that the old masters depicted reality more often than we had hitherto imagined.

Fig. 22. Type of the plate discovered in Gomel and reconstruction of the armour, after Makushnikov and Lupinenko (fig. 2.5, 9). |

An archaeological expedition headed by O. Makushnikov unearthed a burnt, 13th-century armourer's workshop in Gomel, where 1500 plates of lamellar armour were discovered94. These finds allowed reconstruction of some very interesting suits of lamellar, differing from typical armour. As is known, lamellar armour can withstand any weapon, but sword strikes damage its thongs. Masters seem to have always been looking for a method of protecting the suspending thongs, which they did achieve by means of changing the shape of the armour plates95. Sword strikes are not at all dangerous for the lamellar armour of such plates, since the thongs practically never come out onto the surface of the plates96 [fig. 22].

As stated above, lamellar armour of this type with concealed thongs is not rare in Georgian works of art. It is this type of lamellar that St George wears on the Jakhunderi icon of the 11th century97 [fig. 23]; the fortress guard depicted in the miniature at folio 186v of the Jruchi 2nd Tetraevangelion and the archangel on the Labsqaldi icon, probably dating from the 13th century98, are clad in the same type of lamellar armour.

92. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 333-4, pl. 190.

93. CHUBINASHVILI Repoussé, 330-3, pl. 182.

94. MAKUSHNIKOV - LUPINENKO, Lamellar Armour of the Eastern Slav Warrior, 214.

95. LUPINENKO, Splint Armour, 117.

96. MAKUSHNIKOV - LUPINENKO, Lamellar Armour of the Eastern Slav Warrior, 218, fig. 2.5, 9.

97. Once belonged to St George's church in the village of Jakhuderi, now lost, my reasoning is based on Ermakov's photo, N16874. CHUBINASHVILI Repoussé, 352-4, pl. 188; AKHALASHVILI, Inscriptions; 26.

98. AKHALASHVILI, Inscriptions, 72-3, fig. 71.

p81

One type of splint armour, which was evidently for ceremonial use99, clearly shows Georgian influence on Byzantine armour.

M. Parani refers to the emergence of a new type of scale armour in Byzantium in the 12th century, which is characterized by a small central protuberance at the end of the plates. Scales of this type are not observed earlier either in Byzantium, or in Central and Eastern Europe or Western Asia. Parani surmises that similar armour might have penetrated into Byzantium from Georgia100, this assumption is based on three 11th-century Georgian repoussé icons; and, indeed, on the Khidistavi, Sujuna and Bochorma icons St George is depicted in armour with similar protuberances.

In order to further substantiate Parani's view, I intend to list more examples from Georgian reality, which will make it clear that plates with protuberances were more popular in medieval Georgia and chronologically preceded their appearance in Byzantium. At the same time, another issue calls for specification: in my opinion on the Kastoria fresco101 described by Parani, St Demetrius wears a lamellar rather than scale armour. The design of the armour gives ground for this statement: the plates with protuberances are packed close together not overlapping horizontally, the thongs, rivets, rows of leather-lined lamellar are discernable, the cuirass is sleeveless. However, this does not change the essence of the matter, - as we shall become convinced further, in Georgia plates with protuberances are attested with both types of armour and Georgia's primacy causes no doubt.

Like St Demetrius, St George on foot of the 11th-century Bochorma icon102 and St George on foot of Sujuna103 wear a lamellar cuirass comprised of plates with protuberances directed downwards. Careful examination of the armour plates on large-sized representations104, shows that what is depicted on the Bochorma and Sujuna icons is not scale but lamellar armour: thongs running along the entire length of the plates are clearly visible, which

99.The specially decked out, festive character of the armour with protuberances was noticed by Parani in Reconstructing the Reality of Images, 110.

100. However, due to the absence of concrete proofs, she leaves the question open. PARANI, ibid. 111.

101. Depicted in the church of Sts. Anargyroi at Kastoria in c. 1180. PARANI, ibid. pl. 123.

102. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 429-44; Georgian Goldsmithing, 21, pl. 50.

103. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 568; Georgian Goldsmithing, 22, pl. 64.

104. CHUBINASHVILI, Georgian Goldsmithing, pl. 50, 64.

p82

is characteristic of lamellar; neither do the plates overlap horizontally and both cuirasses are sleeveless.

As for the icon of St George of Khidistavi [fig. 24], created in the first third of the 11th century105, its kremasmata and manikia are really composed of scale plates with protuberances, but it is hard to be definite about the cuirass, hence they may be both lamellar and scale armour.

The Archangel Michael painted by Thevdore in the Iprari church in 1096 is clad in kremasmata comprising plates with protuberances directed downward106.

The armour of the Warrior Saint of Pavnisi is formed of laced plates with protuberances directed upwards [fig. 25] 107. The plates directed upwards finally make it clear that there was such a type of lamellar as well and that we are not dealing with the artist's interpretation of scale armour.

The Warrior Saint depicted in Timotesubani at the turn of the 12th-13th centuries also wears a lamellar cuirass comprised of laced plates with protuberances directed downward [fig. 26].

Armour with protuberances is characterized by vertical lines between the plates, which is quite incomprehensible from the viewpoint of a rational design108. If such a structure did exist and it was not the result of the artists' imagination, it should be considered a specimen of excessively complex, decorative and luxurious ceremonial armour.

What conclusion may be drawn from the above-cited specimens of armour? It is quite possible that the great diversity of splint armour, which I have presented, may not correspond to reality and may have often resulted from the artist's imagination. Nevertheless, it must be said definitively that the master's errors alone will not be sufficient to account for such diversity and that a large part of the armour presented here did exist.

105. CHUBINASHVILI, Repoussé, 256-9, pl.153; Georgian Goldsmithing, 22, pl. 53.

106. ALADASHVILI - ALIBEGASHVILI - VOLSKAYA, The Painting School of Svaneti, pl. 25.

107. E. L. PRIVALOVA, Pavnisi, Tbilisi 1977, pl. 15 (in Russian).

108. P Beatson assumes that the presence of dividing lines on the representations can be explained by the fact that the ridged lamellar plates, discovered during the excavations at the great palace in Istanbul, overlapped; unfortunately this assumption cannot account for the presence of lines between the lamellar plates on Georgian icons. P. BEATSON, Byzantine Lamellar Armour: Conjectural Reconstruction of a Find from the Great Palace in Istanbul, Based on Early Medieval Parallels, Varangian Voice 49 (1998) 6.

p83

Now, it would be right to ask the following question: did Georgia influence the development of Byzantine lamellar armour? And, it is indeed hard to find a type of Byzantine armour whose analogue could not be found in Georgia, but if the tables are turned, the picture will be somewhat different. In Byzantium, various types of armour are hard to be found or appear later: lamellar with upper and lower riveting, with riveting between the plates, lamellar with concealed thongs, lamellar entirely directed downward; there are only a few specimens of armour with protuberances; in the 10th-century riveted plates do not occur on Byzantine representations, nor rectangular ones with unrounded top part.

What contributed to such diversity of Georgian armour and advanced technologies? First of all the basic facilitating factor must have been Georgia's geographical location and permanent contacts with the nomadic North109, and with the Iranian-Arabic-Byzantine world in the south, and with various systems of armament; in the 9th-10th centuries a strong impetus to the development of armament must have been given by the emergence on Georgian land of new kingdoms which were engaged in incessant wars with their neighbours; the same can be said about the feudal system that existed in Georgia and the rich and numerous feudal class, which, evidently, encouraged individual experiments with weapons, unlike Byzantium, where the system of armament was on state footing and was distinguished by a high degree of standardization.

It should be said that this situation finds due reflection in technical literature and in the sources. Many foreign authors note the heavy armament of Georgians in the given period110. Yovhannes Draskhanakertc’i describes

109. Nomadic influence is indicated by the relief representation of St Theodore on the western portal in the Nikortsminda church (1010-14), where the Saint wears a long-scale armour, its pattern being reminiscent of the nomads' armour. N. ALADASHVILI, Nikortsminda Reliefs, Tbilisi 1957, pl. 19 (in Georgian). Such a type of long armour was characteristic of Central Asia, whence it spread all over the world. M. GORELIK, Oriental Armour of the Near and Middle East from the Eighth to the Fifteenth Centuries as Shown in Works of Art, in: Islamic Arms and Armour, ed. ROBERT ELGOOD, London 1979, 40.

110. It is significant that in order to illustrate the Byzantine cavalry armament becoming 'heavier' in the 10th century, Western scholars give an example of the heavy armament of the Warrior Saints depicted in the Nikortsminda church, i.e. an example of the armament of Georgia, their neighbor. D. NICOLLE, The Impact of the European Couched Lance on Muslim Military Tradition, The Journal of the Arms and Armour Society 10 (1980) 11.

p84

the army of Western Georgia (the Abkhazian Kingdom) in the 10th century in the following way: A numerous army, with steeds prancing in the air, the warriors wearing iron armour, formidable helmets, cuirasses with nail-studded iron plates and sturdy shields, adornments, spears and swords111. 'The nail-studded iron plates' undoubtedly stand for lamellar cuirass with riveting, with 'the nail' meaning rivet. The 11th-century Byzantine author Michael Attaliates emphasizes the Georgians' heavy armament in the war even with the Byzantines, saying that the courage of Georgians was not only due to their great number, but to the fact that they were protected by the strongest armour and not only they themselves but their armoured and invulnerable horses were also covered (with armour) on all sides112. In the same 11th century, Aristakes Lastivertc’i specially notes the heaviness of the Georgian armament and even says it is the reason of one of their unsuccessful attacks against the Byzantine113.

From this vantage point, it is very interesting to look at the interrelation of Byzantium with its Caucasian (namely, Georgian) neighbours in the matters of armament. In the first place it is worth noting that these relations were fairly close, which facilitated exchange of military technologies114. There is no doubt that the Byzantine military machine exerted considerable influence on its neighbours115, though an opposite phenomenon can also be noticed. Due to its location, Georgia came in touch with the North Caucasian and Central Asian nomads more often than Byzantium, it was

111. Draskhanakertc’i, History of Armenia, ed. E. TSAGAREISHVILI, Tbilisi 1965, 257 (in Georgian). Here I take an opportunity and thank E. Kvachantiradze for comparing the translation with the Armenian original and checking its accuracy.

112. Attaliates, History, ed. S. QAUKHCHISHVILI, Tbilisi 1966, 27 (in Georgian). I thank K. Nizharadze for the new, precise translation of the passage. Michaelis Attaliotae Historia, ed. I. BEKKER, Bonn 1853, 234.

113. Lastivertc’i, History, ed. E. TSAGAREISHVILI, Tbilisi 1974, 51 (in Georgian).

114. Discussion of Georgian-Byzantine relations would lead us too far. They were especially intensive in the period under discussion and were characterized by joint battles against the Arabs, participation of Georgians in the civil wars in Byzantium and, finally, almost a century-long confrontation with each other.

115. Nevertheless, Georgian military terminology came under a stronger influence of the Persian and Arabic languages.

p85

via Georgia that some novelties in their armament, direct or transformed, may have found their way to Byzantium116.

In spite of all that has been said above, as I have already noted, in the absence of archaeological evidence and on the strength of only iconographic data, it is difficult to give a positive answer to the question that has been posed and to assert anything definitively. At the same time it can be said without any doubt that Georgia can be considered one of the major centers of the manufacture of splint armour and of innovations, and that some of the types of armour widespread in Byzantium, may have originated there.

116. In D. Nicolle's view, the lamellar penetrated into Iran from Central Asia, subsequently spreading to the Caucasus and Anatolia. D. NICOLLE, The Military Technology of Classical Islam, Thesis Presented to the university of Edinburgh for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (1982) 173.

Fig. 1. Shadows under the plates on the skirt of the Warrior Saint in Timotesubani are expressed as a brown line by the artist, but on the lamellar cuirass both the bands and shadows can be seen. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 4. Saint from Timotesubani clad in the traditional lamellar cuirass. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 5. St George of Chukuli in the lamellar backed with leather, after Chubinashvili (pl. 46).

Fig. 6. St George of Chikhareshi in the armour with two rivets, after Chubinashvili (pl. 47).

Fig. 7. St George of Nakuraleshi in the lamellar with two rivets, after Chubinashvili (pl. 42).

Fig. 8. St Procopius in the lamellar with two rivets. Manuscript A648, p. 60r, National Centre of Manuscripts of Georgia.

Fig. 10. St George clad in the linear lamellar with double riveting on the Mravaldzali icon. (photo by Ermakov).

Fig. 11. St George of Parakheti in the linear lamellar with double riveting. (photo by Ermakov).

Fig. 12. St George of Nakipari clad in the ‘inverted’ lamellar with double riveting. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 13. St George of Ipari in the banded lamellar without riveting, after Chubinashvili (pl. 184).

Fig. 14. St George of Labechina in the banded lamellar with two rivets, after Chubinashvili (pl. 181).

Fig. 15. St George of Supi in the banded ‘inverted’ lamellar with riveting. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 16. St George of Supi, in the typical banded lamellar with riveting. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 17. Warrior Saint (St Theodore?) of Adishi in the typical banded lamellar with riveting. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 18. St Theodore of Lagurka, well-preserved representation of the lamellar with riveting between the plates. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 19. St Panteleimon on the processional cross of Pari. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 21. St George in the lamellar with rectangular plates on the façade of the Adishi church. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Fig. 23. St George of Jakhunderi in the lamellar with concealed thongs, after Chubinashvili (pl. 188).

Fig. 24. St George of Khidistavi in the lamellar with protuberances, after Chubinashvili (pl. 153).

Fig. 25. Warrior Saint of Pavnisi in the lamellar with protuberances, after Privalova (pl. 15).

Fig. 26. Warrior Saint of Timotesubani in the lamellar with the protuberances oriented downward. (photo by S. Sarjveladze).

Source: Byzantina Symmeikta